If you've ever wondered what your dog is thinking, Stein's third novel offers an answer. Enzo is a lab terrier mix plucked from a farm outside Seattle to ride shotgun with race car driver Denny Swift as he pursues success on the track and off. Denny meets and marries Eve, has a daughter, Zoë, and risks his savings and his life to make it on the professional racing circuit. Enzo, frustrated by his inability to speak and his lack of opposable thumbs, watches Denny's old racing videos, coins koanlike aphorisms that apply to both driving and life, and hopes for the day when his life as a dog will be over and he can be reborn a man. When Denny hits an extended rough patch, Enzo remains his most steadfast if silent supporter. Enzo is a reliable companion and a likable enough narrator, though the string of Denny's bad luck stories strains believability. Much like Denny, however, Stein is able to salvage some dignity from the over-the-top drama.

Sittenfeld tracks, in her uneven third novel, the life of bookish, naïve Alice Lindgren and the trajectory that lands her in the White House as first lady. Charlie Blackwell, her boyishly charming rake of a husband, whose background of Ivy League privilege, penchant for booze and partying, contempt for the news and habit of making flubs when speaking off the cuff, bears more than a passing resemblance to the current president (though the Blackwells hail from Wisconsin, not Texas). Sittenfeld shines early in her portrayal of Alice's coming-of-age in Riley, Wis., living with her parents and her mildly eccentric grandmother. A car accident in her teens results in the death of her first crush, which haunts Alice even as she later falls for Charlie and becomes overwhelmed by his family's private summer compound and exclusive country club membership. Once the author leaves the realm of pure fiction, however, and has the first couple deal with his being ostracized as a president who favors an increasingly unpopular war, the book quickly loses its panache and sputters to a weak conclusion that doesn't live up to the fine storytelling that precedes it.

This ambitious third novel tells two parallel stories of polygamy. The first recounts Brigham Young's expulsion of one of his wives, Ann Eliza, from the Mormon Church; the second is a modern-day murder mystery set in a polygamous compound in Utah. Unfolding through an impressive variety of narrative forms—Wikipedia entries, academic research papers, newspaper opinion pieces—the stories include fascinating historical details. We are told, for instance, of Brigham Young's ban on dramas that romanticized monogamous love at his community theatre; as one of Young's followers says, "I ain't sitting through no play where a man makes such a cussed fuss over one woman." Ebershoff demonstrates abundant virtuosity, as he convincingly inhabits the voices of both a nineteenth-century Mormon wife and a contemporary gay youth excommunicated from the church, while also managing to say something about the mysterious power of faith.

tells the remarkable WWII story of Jan Zabinski, the director of the Warsaw Zoo, and his wife, Antonina, who, with courage and coolheaded ingenuity, sheltered 300 Jews as well as Polish resisters in their villa and in animal cages and sheds. Using Antonina's diaries, other contemporary sources and her own research in Poland, Ackerman takes us into the Warsaw ghetto and the 1943 Jewish uprising and also describes the Poles' revolt against the Nazi occupiers in 1944. She introduces us to such varied figures as Lutz Heck, the duplicitous head of the Berlin zoo; Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, spiritual head of the ghetto; and the leaders of Zegota, the Polish organization that rescued Jews. Ackerman reveals other rescuers, like Dr. Mada Walter, who helped many Jews pass, giving lessons on how to appear Aryan and not attract notice. Ackerman's writing is viscerally evocative, as in her description of the effects of the German bombing of the zoo area: ...the sky broke open and whistling fire hurtled down, cages exploded, moats rained upward, iron bars squealed as they wrenched apart. This suspenseful beautifully crafted story deserves a wide readership. 8 pages of illus.

Newspaper columnist Corrigan was a happily married mother of two young daughters when she discovered a cancerous lump in her breast. She was still undergoing treatment when she learned that her beloved father, who'd already survived prostate cancer, now had bladder cancer. Corrigan's story could have been unbearably depressing had she not made it clear from the start that she came from sturdy stock. Growing up, she loved hearing her father boom out his morning HELLO WORLD dialogue with the universe, so his kids would feel like the world wasn't just a safe place but was even rooting for you. As Corrigan reports on her cancer treatment—the chemo, the surgery, the radiation—she weaves in the story of how it felt growing up in a big, suburban Philadelphia family with her larger-than-life father and her steady-loving mother and brothers. She tells how she met her husband, how she gave birth to her daughters. All these stories lead up to where she is now, in that middle place, being someone's child, but also having children of her own. Those learning to accept their own adulthood might find strength—and humor—in Corrigan's feisty memoir.

Tired of always dreaming and never doing, Cici, Lindsay, and Bridget make a life-altering decision. Uprooting themselves from their comfortable lives in the suburbs, the three friends buy a run-down mansion, nestled in the picturesque Shenandoah Valley. They christen their new home “Ladybug Farm,” hoping that the name will bring them luck.

As the friends take on a home improvement challenge of epic proportions, they encounter disaster after disaster, from renegade sheep and garden thieves to a seemingly ghostly inhabitant. Over the course of a year, overwhelming obstacles make the three women question their decision, but they ultimately learn that sometimes the best things can happen when everything goes wrong…

A sad, absorbing story about the disintegration and rejoining of an Iowa farm family. Mack Barnes knows that family farms are essentially extinct, but he cannot bear to lose his land. He tries farming at night for a while and working for the school district during the day. Inevitably, he crashes and falls into a deep depression. As the story opens, Mack returns from the hospital to an embittered wife, Jodie, who is about to begin an affair; a son, Taylor, who is fascinated with all things Goth; a daughter, Kedzie, who has become a Jesus freak; and Rita, Mack's quintessential Iowa mom, who scurries about her dwindling village doing good deeds. Wright's scenes move along almost magically, with "the horizon of the entire world close at hand." Her feel for an Iowa farm town is achingly precise. There is indeed a Christian message here, but it isn't easy or obvious, and when the novel draws toward its climax of muted hope, you know how painful a passage these good people have undergone.

Umrigar's schematic novel (after Bombay Time) illustrates the intimacy, and the irreconcilable class divide, between two women in contemporary Bombay. Bhima, a 65-year-old slum dweller, has worked for Sera Dubash, a younger upper-middle-class Parsi woman, for years: cooking, cleaning and tending Sera after the beatings she endures from her abusive husband, Feroz. Sera, in turn, nurses Bhima back to health from typhoid fever and sends her granddaughter Maya to college. Sera recognizes their affinity: "They were alike in many ways, Bhima and she. Despite the different trajectories of their lives—circumstances... dictated by the accidents of their births—they had both known the pain of watching the bloom fade from their marriages." But Sera's affection for her servant wars with ingrained prejudice against lower castes. The younger generation—Maya; Sera's daughter, Dinaz, and son-in-law, Viraf—are also caged by the same strictures despite efforts to throw them off. In a final plot twist, class allegiance combined with gender inequality challenges personal connection, and Bhima may pay a bitter price for her loyalty to her employers. At times, Umrigar's writing achieves clarity, but a narrative that unfolds in retrospect saps the book's momentum.

The plot of Anna Quindlen's novel Blessings is constructed on the same model as E.T.: adorable orphaned creature is found by unlikely caregiver who against his or her better judgment falls in love with the little beast, while all the while, the authorities loom in the background, threatening to take the foundling away. In Quindlen's book, however, the foundling in question isn't an alien, but a squalling baby left at Blessings, a vast estate owned by an ancient, crabby matriarch named Lydia Blessing. By a fluke, the baby's parents abandon her by the garage rather than at the front door, and so she is discovered by Skip Cuddy, Lydia Blessing's newly hired handyman, who happens to be an ex-con. The plot proceeds from there in fairly E.T.-like fashion, minus the Reese's Pieces and flying bicycles. Skip, Lydia, and the baby they name Faith form a surprisingly loving and sustaining, albeit temporary, family unit.

Quindlen wrings a remarkable amount of pathos from this somewhat simple setup. One of her strengths as a writer is the quietness she brings to her story; family secrets of paternity and lost love are buried deep in the narrative, hidden in descriptive paragraphs where they subtly zing us with their news. Her ear is good, too: we believe Skip and his bad-boy friends when they're shooting the breeze. Best of all is her flair for observation. The book wouldn't work at all if she couldn't make us feel Skip and Lydia's amazement at the small joys of a baby ("The deep pleat in the fat at her elbow made her arms look muscled"). Here is a book that lives up to its title.

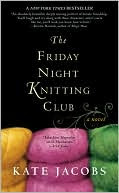

Georgia Walker's entire life is wrapped up in running her knitting store, Walker and Daughter, and caring for her 12-year-old daughter, Dakota. With the help of Anita, a lively widow in her seventies, Georgia starts the Friday Night Knitting Club, which draws loyal customers and a few oddballs. Darwin Chiu, a feminist grad student, believes knitting is downright old-fashioned, but she's drawn to the club as her young marriage threatens to unravel. Lucie, 42, a television producer, is about to become a mother for the first time--without a man in her life. Brash book editor KC finds her career has stalled unexpectedly, while brilliant Peri works at Walker and Daughter by day and designs handbags at night. Georgia gets her own taste of upheaval when Dakota's father reappears, hoping for a second chance. The yarn picks up steam as it draws to a conclusion, and an unexpected tragedy makes it impossible to put down. Jacobs' winning first novel is bound to have appeal among book clubs.

Cassie Shaw, the 30-year-old dyslexic high school dropout narrator of Kaufman and Mack's follow-up to Literacy and Longing in L.A., is devoid of self-esteem and, as the winsome novel opens, has just been widowed by a jerk who left her nothing but debt. Desperate for a job, Cassie fudges her education background on a job application and snags an entry-level university office job working under William Conner, a charismatic professor of animal behavior who ignites Cassie's desire for learning—and other things. As Cassie's lust for knowledge swells and she becomes more involved with Conner, the list of her deceptions lengthens, and it's only a matter of time until budding beau Conner finds out. Kaufman and Mack lace the narrative with light humor (the rats in California's Topanga Canyon are like roaches in NY or liars in LA) and nods to Emerson, Whitman, Thoreau, Plato and Keats. Delightfully merging humor, philosophy and reflections on nature, this novel is a lot of fun and might give some readers freshman-year flashbacks.

Moriarty's follow-up to book-group favorite The Center of Everything again explores a tense, fragile mother-daughter relationship, this time finding sharper edges where personal history and parenting meet. Now a junior high school English teacher married to a college professor, Leigh has spent much of her adult life trying to distance herself from her dysfunctional childhood. Raising their two children in a small, safe Kansas town not far from where Leigh and her troubled sister, Pam, were raised by their single mother, Leigh finds her good fortune still somewhat empty. Daughter Kara, 18 and a high school senior, is distant; sensitive younger son Justin is unpopular; Leigh can't seem to reach either—Kara in particular sees Leigh (rightly) as self-absorbed. When Kara accidentally hits and kills another high school girl with the family's car, Leigh is forced to confront her troubled relationship with her daughter, her resentment toward her husband (who understands Kara better) and her long-buried angst about her own neglectful mother. The intriguing supporting characters are limited by not-very-likable Leigh's POV, but Moriarty effectively conveys Leigh's longing for escape and wariness of reckoning.

When her mother is diagnosed with cancer, New Yorker Emily Rhode ditches her too-perfect boyfriend and far from perfect legal career to become her mother's primary caregiver. At the same time, she reconciles with her estranged father, who left when she was five. When he offers her a job as a receptionist at his law firm, complete with Friday martini lunch dates and father-daughter cab rides to work, Emily agrees, and jokey family bonding follows as mom skates through treatment and dad proves to be more of a teddy bear than an iceman. Davis, author of Girls' Poker Night and a former writer for The Late Show with David Letterman, loads the narrative with one-liner asides and funny riffs (there's a particularly good bit about espresso machines), though she's less adept at sizing up Emily's inner turmoil, notably her fear of committing to smart, patient and loving boyfriend Sam. Though soft-focused (taking care of cancer-stricken mom mostly consists of watching TV and playing board games), Davis's book leavens regret and tragedy with a light-handed wit.

No comments:

Post a Comment